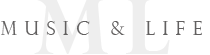

Here’s the uncomfortable truth that every central banker secretly knows but won’t admit at cocktail parties: cutting interest rates to fight inflation is like trying to put out a fire with gasoline. It might feel like you’re doing something dramatic and decisive, but you’re actually making the problem worse. This isn’t just economic theory, it’s historical fact backed by decades of real-world disasters.

Value Proposition: Learn why the conventional wisdom about rate cuts is backwards, how to position your investments when central banks inevitably make this mistake, and which countries prove that monetary policy can’t defy economic gravity.

The Great American Inflation Comedy Show: 1970s Edition

Let me take you back to the 1970s, when America’s central bankers thought they could have their cake and eat it too. The Federal Reserve spent most of the decade playing monetary policy whack-a-mole, cutting rates whenever unemployment ticked up and then acting surprised when inflation exploded higher.

Value Proposition: Understand how the “stop-go” monetary policy of the 1970s created the blueprint for modern central bank failures.

The numbers tell the story better than any economics textbook. In 1965, inflation was running at a manageable 1.6%. By 1974, it hit 11%. By 1979, it reached 13.5%. The Fed’s response? A series of half-hearted rate increases followed by immediate retreats whenever the economy showed signs of weakness. It was like watching someone try to lose weight by alternating between crash diets and binge eating.

Paul Volcker finally ended this monetary madness in 1979 by doing something radical: actually fighting inflation instead of pretending it would go away on its own. He jacked rates up to 20% and kept them there until inflation screamed for mercy. The result? A brutal recession, but inflation finally collapsed from double digits to the low single digits where it stayed for decades.

Investment Implication: When central banks finally get serious about fighting inflation, they create massive opportunities in sectors that benefit from high real interest rates. Financial services, mature value companies, and commodity plays all outperformed during Volcker’s tightening cycle.

Japan’s Lost Decades: When Rate Cuts Become Economic Quicksand

If you want to see what happens when a country becomes addicted to low interest rates, Japan wrote the definitive manual between 1990 and 2020. After their asset bubble burst in 1990, Japanese policymakers made a classic mistake: they assumed lower interest rates would magically restore economic growth.

Value Proposition: Learn how Japan’s three-decade experiment with ultra-low rates proves that monetary policy can’t fix structural economic problems.

The Bank of Japan cut rates from 6% in 1990 to effectively zero by 1999. Did this cure Japan’s economic malaise? Not exactly. Instead of spurring growth, ultra-low rates created a deflationary spiral where consumers delayed purchases expecting lower prices tomorrow, businesses hoarded cash instead of investing, and the entire economy got stuck in neutral.

Here’s the really painful part: Japan’s nominal GDP in 2020 was roughly the same as it was in 1995, despite three decades of the most accommodative monetary policy in modern history. Real wages fell 11% over this period. The debt-to-GDP ratio exploded from reasonable levels to over 200% as the government tried to compensate for monetary policy’s failures with fiscal stimulus.

Investment Insight: Japan’s experience shows that when rate cuts stop working, governments resort to increasingly desperate measures. Currency debasement, asset purchases, and negative interest rate policies become the new normal, creating opportunities in hard assets and international diversification strategies.

Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation Horror Show: When Money Printing Goes Full Weimar

For the ultimate case study in why monetary policy can’t solve everything, let’s visit Zimbabwe circa 2000-2008. The government faced a classic policy dilemma: falling tax revenues from agricultural collapse and rising spending needs. Their solution? Print money and keep interest rates artificially low to “stimulate” the economy.

Value Proposition: Understand how Zimbabwe’s collapse demonstrates the extreme endpoint of accommodative monetary policy when underlying economic fundamentals deteriorate.

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe kept real interest rates negative throughout the early 2000s while printing money to finance government operations. By 2007, inflation hit hyperinflation territory, eventually reaching an estimated 79.6 billion percent monthly in November 2008. A loaf of bread cost 10 billion Zimbabwe dollars, and ATMs couldn’t handle transactions because their software couldn’t process numbers with that many zeros.

The tragic irony? Throughout this period, policymakers kept insisting that lower borrowing costs would revive economic activity. Instead, negative real interest rates encouraged currency speculation, capital flight, and economic collapse. People stopped using Zimbabwe dollars entirely, conducting business in US dollars and South African rand despite government prohibitions.

Trading Opportunity: Zimbabwe’s experience shows how currency collapses create massive dislocations in asset values. Real estate, stocks, and commodities priced in collapsing currencies often become incredibly cheap for investors with access to hard currency.

Turkey’s Modern Monetary Experiment: Erdogan vs Economic Reality

For a contemporary example of rate cuts making inflation worse, Turkey under President Erdogan provides a masterclass in how political pressure can override economic sense. Despite inflation running well above target, Erdogan has repeatedly forced the Turkish central bank to cut rates, insisting that high interest rates cause inflation rather than cure it.

Value Proposition: See how political interference in monetary policy creates predictable investment opportunities for those willing to bet against wishful thinking.

Turkish inflation hit 85% in October 2022 while the central bank was cutting rates from 19% to 9%. The Turkish lira collapsed against the dollar, making imports more expensive and feeding back into higher domestic inflation. The government’s response? More rate cuts and increasingly desperate capital controls to prevent currency flight.

The mechanism is brutally simple: when you cut rates while inflation is rising, real interest rates turn negative. This encourages borrowing to buy real assets, creating asset bubbles. It discourages saving in the domestic currency, causing capital flight. The currency weakens, import prices rise, and inflation accelerates. Rinse and repeat until something breaks.

Investment Strategy: Turkey’s experience shows how currency crises create opportunities in neighboring countries’ assets, multinational companies with local subsidiaries that can benefit from competitive devaluations, and hard currency bonds issued by the collapsing country.

The Weimar Republic: History’s Most Famous Monetary Policy Disaster

No discussion of monetary policy failures would be complete without visiting 1920s Germany, where the government’s response to war reparations and economic collapse was to print money and keep borrowing costs low. German policymakers genuinely believed that monetary accommodation would restore economic activity and solve their fiscal problems.

Value Proposition: Understand how the Weimar hyperinflation provides the template for how democracies destroy their currencies when facing impossible fiscal arithmetic.

The German government kept real interest rates negative throughout the early 1920s while printing marks to pay workers, fund government operations, and meet reparations demands. By 1923, prices were doubling every few days. A US dollar was worth 4.2 trillion marks at the peak. Workers were paid twice daily because money lost value so quickly between morning and evening.

The inflation only ended when Germany introduced a new currency backed by real assets and abandoned the policy of monetary accommodation. The economic lesson was clear: you can’t print your way to prosperity, and cutting rates during inflationary periods only makes the problem worse.

Historical Investment Lesson: During hyperinflation, German investors who held foreign currency, real estate, or equity stakes in productive businesses preserved wealth. Those who held cash or bonds denominated in marks were wiped out completely.

Hungary 1946: When Rate Cuts Become Economic Suicide

For the most extreme example of accommodative monetary policy gone wrong, Hungary in 1946 experienced the worst hyperinflation in recorded history. The government kept interest rates artificially low while printing money to fund reconstruction after World War II.

Value Proposition: Learn how Hungary’s experience shows that there are no exceptions to the laws of monetary economics, regardless of special circumstances or political justifications.

Hungarian inflation in July 1946 reached 41.9 quadrillion percent, with prices doubling every 15 hours. The government issued a 100 quintillion pengő banknote, the highest denomination currency ever printed. By the end, people were literally using cash as wallpaper because it was cheaper than buying actual wallpaper.

Throughout this period, government economists insisted that low interest rates were necessary to stimulate economic recovery. Instead, negative real rates encouraged speculation, currency substitution, and complete economic breakdown. The crisis only ended when Hungary abandoned its currency and monetary accommodation policies entirely.

The Economic Logic: Why Rate Cuts Fuel Inflation

Understanding why rate cuts worsen inflation requires grasping basic economic incentives. When central banks cut rates while inflation is rising, they create negative real interest rates. This means borrowers are effectively being paid to take on debt, while savers are being punished for holding cash.

Value Proposition: Master the relationship between real interest rates and inflationary incentives to predict central bank policy failures before they happen.

Negative real rates encourage borrowing to buy real assets, driving up prices. They discourage saving in the domestic currency, causing capital flight and currency weakness. Import prices rise due to currency depreciation, feeding back into domestic inflation. Meanwhile, the signal that rates are being cut during inflation tells markets that the central bank isn’t serious about price stability.

The perverse incentive structure becomes self-reinforcing. As inflation rises and rates stay low, real rates become more negative, encouraging more speculative behavior and currency flight. The central bank faces political pressure to keep cutting rates to “support growth,” making the problem worse.

Investment Strategies for Central Bank Policy Mistakes

When central banks make the mistake of cutting rates during inflationary periods, they create predictable trading opportunities for investors who understand the dynamics.

Value Proposition: Position your portfolio to profit from central bank policy errors rather than become a victim of them.

Currency strategies become obvious: short the domestic currency against hard currencies or commodity-backed alternatives. Real assets like real estate, commodities, and inflation-protected securities outperform. International diversification becomes critical as domestic purchasing power erodes.

Equity strategies favor companies with pricing power, hard asset exposure, or foreign currency earnings. Financial services companies eventually benefit when reality forces interest rates higher. Export-oriented businesses gain competitiveness from currency weakness, though they may struggle initially with higher input costs.

Bond strategies require extreme caution. Domestic government bonds become toxic as inflation erodes real returns. Corporate bonds fare slightly better if they offer inflation protection or floating rates. Foreign currency bonds provide both yield and currency appreciation potential.

The Political Economy of Monetary Accommodation

Understanding why central banks make these obvious mistakes requires appreciating the political pressures they face. Rate cuts provide immediate economic relief and political benefits, while the inflationary consequences take months or years to fully manifest.

Value Proposition: Predict central bank policy errors by understanding the political incentives that drive obviously bad economic decisions.

Politicians love rate cuts because they boost asset prices, reduce borrowing costs, and create the illusion of economic stimulus. The inflation that follows can be blamed on external factors, supply chains, or greedy businesses. By the time the full consequences become undeniable, the politicians who made the decisions may be out of office.

Central bankers face enormous pressure to accommodate fiscal policy mistakes rather than force governments to make difficult choices. It’s politically easier to cut rates and hope inflation goes away than to trigger a recession by tightening monetary policy. This creates a bias toward accommodation even when economic logic demands restraint.

Modern Applications: Fed Policy in the 2020s

The Federal Reserve’s recent experience provides a contemporary example of these dynamics playing out in real time. After cutting rates to zero during the pandemic and promising to keep them there, the Fed was slow to acknowledge that inflation wasn’t “transitory.”

Value Proposition: Apply historical lessons to current Fed policy to position for the inevitable policy corrections that market pricing hasn’t fully discounted.

The Fed’s initial response to rising inflation in 2021 was to insist that rate cuts and quantitative easing weren’t causing price pressures. When inflation reached 9.1% in June 2022, they finally started raising rates, but only after losing significant credibility. The pattern matches historical examples where central banks deny problems until they become undeniable.

Current market expectations for aggressive Fed easing in 2025-2026 may repeat historical mistakes if inflation proves more persistent than policymakers expect. Understanding this dynamic creates opportunities for investors positioned correctly for monetary policy errors.

The Bottom Line: Economic Gravity Always Wins

Every historical example reaches the same conclusion: you cannot cut interest rates to fight inflation any more than you can jump off a building to fight gravity. The laws of economics aren’t suggestions, they’re as fundamental as physical laws.

Value Proposition: Develop the intellectual framework to avoid being swept up in popular monetary policy narratives that contradict basic economic principles.

Central banks that try to accommodate fiscal irresponsibility and structural economic problems through rate cuts invariably make inflation worse. The process may take months or years, but the outcome is always the same: eventually, reality reasserts itself, and policymakers are forced to abandon accommodation.

The investment implications are clear: when central banks cut rates during inflationary periods, position for currency weakness, asset price inflation, and eventual policy reversals. History provides the playbook for how these episodes unfold, and the ending is always the same.

Understanding this dynamic isn’t just academic knowledge, it’s practical wisdom that can preserve and grow wealth during periods when monetary policy loses touch with economic reality. The central bankers may not learn from history, but smart investors can profit from their predictable mistakes.